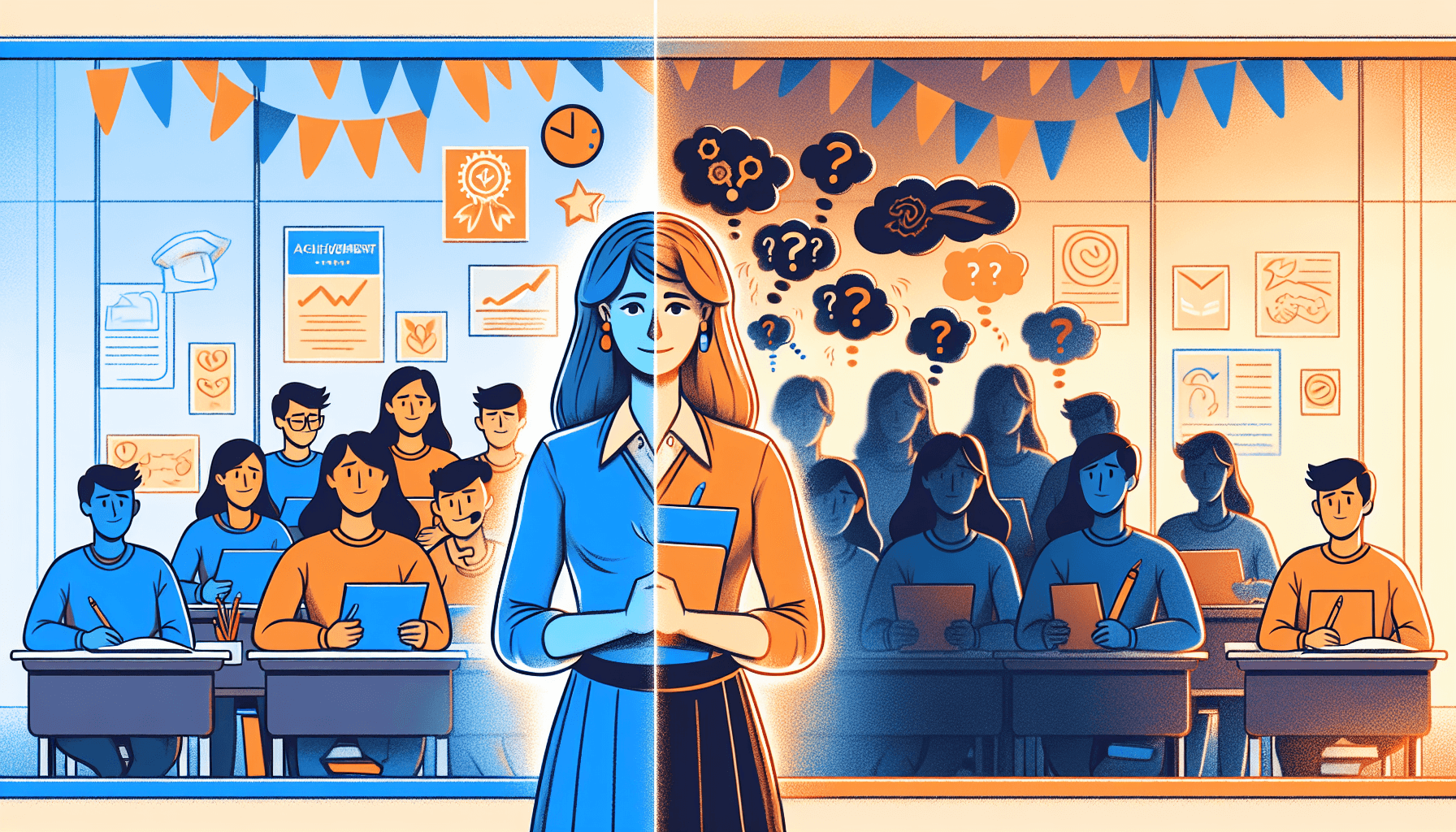

We've all seen it happen. You help a student solve a problem, she gets it right. Next day, she can't do the same type of problem alone. Your help didn't build understanding. It created reliance.

Scaffolding is supposed to prevent this. When done well, it builds independence. When done poorly, it creates dependence that masquerades as learning.

What Is Scaffolding in Teaching?

Scaffolding is temporary, strategic support that helps students achieve learning goals they cannot reach independently - yet.

The term comes from construction. Workers erect scaffolding to build structures, then remove it once the building stands on its own. Educational scaffolding works the same way. You provide structured support, then systematically remove it as students develop competence.

This isn't just "helping students." Scaffolding is intentional, planned, and designed to fade. The support serves a specific purpose: bridging the gap between what students can do alone and what they need to learn next.

The key distinction: Scaffolds are temporary by design. If support stays permanently, it's an accommodation or modification, not scaffolding. True scaffolding aims for independence.

Scaffolding Theory and Its History

The concept draws from Lev Vygotsky's work on how people learn. Vygotsky identified what he called the Zone of Proximal Development - the space between what a learner can do alone and what they can accomplish with guidance. Learn more: Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory

Learning happens most effectively in this zone. Too easy and students don't grow. Too hard and they can't engage meaningfully. Just right - challenging but achievable with support - creates optimal conditions for learning.

Effective scaffolding operates precisely within this zone. You provide support that challenges without overwhelming.

The term "scaffolding" itself came later, coined by Jerome Bruner in the 1970s. But the underlying principles reflect Vygotsky's insights about how social interaction enables cognitive development.

This theoretical foundation emphasizes something important: learning is social before it becomes individual. Students benefit from interaction with more knowledgeable others who can model thinking, ask probing questions, and provide feedback.

Eventually, what students do with support becomes what they can do alone. External scaffolds become internal capabilities.

Core Principles of Effective Scaffolding

Successful scaffolding rests on several fundamental principles that distinguish it from other forms of support.

Intentional and Temporary

Scaffolds serve a specific purpose and include a clear removal plan. You don't just help students - you help them with the explicit goal of not needing your help eventually.

This temporary nature requires planning. Before providing support, consider: What does this scaffold enable? How will I know when to remove it? What does independence look like?

The key lies in timing. Remove scaffolds too quickly and you frustrate learners. Maintain them too long and you create dependence. The art of teaching involves reading student readiness for increased independence.

Responsive to Individual Needs

Quality scaffolding adapts to each student's current understanding. What works for one learner may not suit another.

This responsiveness demands ongoing observation and adjustment. You watch student responses, listen to their questions, and modify support accordingly. Some students need visual scaffolds, others benefit from verbal cues, many require combinations.

The industrial model of education assumes all students need the same support at the same time. Scaffolding theory recognizes that learners arrive with different prior knowledge, skills, and experiences. Support must match actual needs, not grade-level assumptions. Explore individualized approaches: Student-Centered Learning

Promotes Active Learning

Scaffolding isn't about making tasks easier. It's about making challenging tasks accessible through strategic support.

Good scaffolds guide students through thinking processes while requiring their participation and effort. The work remains demanding - scaffolds just make it doable.

This active engagement develops metacognitive skills as students learn to monitor their own understanding and apply strategies independently. They become aware of their learning processes and develop confidence tackling new challenges.

Bad scaffolding does the thinking for students. Good scaffolding supports students doing their own thinking.

Fades Systematically

The gradual release of responsibility provides a framework for systematic scaffold removal. In properly implemented scaffolding, this progression typically follows:

- I do, you watch: Teacher demonstrates while thinking aloud, making expert thinking visible.

- We do together: Teacher and students work collaboratively with high support and frequent checking.

- You do together: Students work with peers while teacher observes and provides targeted support.

- You do alone: Students work independently while teacher monitors and intervenes only if needed.

Each phase reduces teacher support while increasing student responsibility. The goal is always independence.

Types of Scaffolding Strategies

Different learning situations call for different scaffolding approaches.

Modeling and Think-Alouds

You demonstrate how to approach a task while verbalizing your thinking process. This makes expert thinking visible to novices.

For example, when teaching close reading: "I notice the author used the word 'however' here. That signals a contrast coming. Let me reread the previous sentence to understand what's being contrasted..."

Students can't see inside your head. Think-alouds open that window. They learn not just what to do, but how to think about doing it.

Questioning Scaffolds

Strategic questions guide student thinking without providing answers. Different question types serve different purposes:

Clarifying questions: "What do you mean by...?" "Can you say more about...?"

Probing questions: "What makes you think that?" "What evidence supports this?"

Redirecting questions: "How does this connect to what we learned earlier?" "What's another way to approach this?"

Good questions do cognitive work - they scaffold thinking processes students will eventually internalize.

Graphic Organizers and Visual Supports

Visual structures help students organize information and see relationships. These might include:

- Concept maps for showing connections between ideas

- Venn diagrams for comparing and contrasting

- Flow charts for sequential processes

- T-charts for organizing information into categories

Visual scaffolds are particularly powerful because they externalize thinking processes. Students can see and manipulate their thoughts, making abstract reasoning more concrete.

Worked Examples and Models

You provide examples of completed work that illustrate quality and process. Students analyze these models to understand expectations before producing their own work.

For writing, this might mean examining a well-constructed paragraph before drafting. For math, it means studying solved problems before attempting similar ones.

Models answer the question: "What does good look like?" Without this reference point, students struggle to evaluate their own work or know what to aim for.

Sentence Frames and Language Supports

You provide language structures that help students express complex thinking, especially valuable for English learners and students developing academic language.

For example: "The evidence suggests _____ because _____." "While _____ is true, it's also important to consider _____."

These frames scaffold language production while students develop content understanding. Eventually, students internalize the structures and use them independently.

Chunking Complex Tasks

You break large, complex tasks into smaller, manageable pieces. Each piece becomes achievable, and completion of smaller steps builds momentum and confidence.

For a research paper, scaffolding might include: selecting a topic, generating questions, finding sources, taking notes, outlining, drafting sections, revising, and editing - each step taught and practiced separately before combining them.

Chunking prevents overwhelm while ensuring students learn the complete process, not just the final product.

Collaborative Structures

You design group work where students scaffold learning for each other. Peer explanation, peer feedback, and collaborative problem-solving provide multiple sources of support. Explore group structures: Cooperative Learning

Students often explain concepts differently than teachers do, sometimes making ideas more accessible to peers. The student who explains also benefits - teaching others deepens understanding.

But effective peer scaffolding requires explicit instruction. Students need to learn how to give useful feedback, listen actively, and work productively together.

Scaffolding Across Subject Areas

Scaffolding principles apply universally, but implementation looks different across disciplines.

Mathematics Scaffolding

Math scaffolding often involves:

- Concrete-representational-abstract progression: Start with physical manipulatives, move to visual representations, finally work with abstract symbols.

- Worked examples with fading: Show complete solutions, then partially completed problems, then just the setup, finally independent work.

- Number sense tools: Number lines, hundreds charts, fraction bars make abstract concepts visible and easy to manipulate.

- Process scaffolds: Step-by-step procedures, graphic organizers for problem-solving, sentence frames for mathematical reasoning.

The goal isn't just getting right answers. It's developing mathematical thinking that transfers to new problems.

Literacy Scaffolding

Reading and writing scaffolds include:

- Before reading: Activating prior knowledge, previewing text structure, pre-teaching vocabulary, establishing purpose.

- During reading: Annotation guides, comprehension monitoring questions, graphic organizers for note-taking.

- After reading: Discussion protocols, summary frames, response templates.

- For writing: Brainstorming structures, organization frameworks, sentence starters, revision checklists, peer feedback protocols.

Literacy scaffolds make complex texts accessible while building skills for reading and writing independently. Learn about deeper comprehension: Cognitive Learning Theory

Science and Social Studies Scaffolding

Content area scaffolds help students access complex information and think disciplinarily:

- Vocabulary supports: Word walls, graphic organizers for terms, context clue strategies.

- Text structures: Guides for analyzing cause-and-effect, comparison, problem-solution, sequence.

- Thinking frameworks: Scientific method templates, historical thinking charts, claim-evidence-reasoning organizers.

- Background knowledge building: Video introductions, picture walks, advance organizers connecting new content to prior learning.

These scaffolds help students think like scientists and historians while building content knowledge.

The Challenge of Knowing When to Remove Scaffolds

This is where scaffolding gets hard. Provide support too long and you create dependence. Remove it too soon and you set students up for failure.

Signs Students Are Ready for Less Support

Watch for these indicators:

- Completion without hesitation: Students start tasks confidently without seeking immediate help.

- Self-correction: Students catch and fix their own errors before you point them out.

- Transfer: Students apply strategies to new situations without prompting.

- Explaining to others: Students can articulate their thinking process to peers.

- Reduced errors: Accuracy increases on similar tasks.

- Speed improvement: Students complete tasks more quickly as processes become automatic.

The Gradual Withdrawal Process for Scaffolds

Don't remove all scaffolds at once. Systematic fading works better:

- Reduce frequency of support while maintaining quality

- Delay your response time - wait for students to attempt first

- Make scaffolds less specific - broader hints rather than detailed steps

- Shift from teacher to peer support

- Move from external tools to internalized strategies

This gradual process builds confidence while developing independence.

When Scaffolds Need to Return

Sometimes students need scaffolds reintroduced, and that's okay. This isn't failure - it's responsive teaching.

New difficulty levels, increased complexity, novel contexts, or challenging content may require temporarily increasing support. This is normal and expected.

The key is being deliberate. You're not abandoning scaffolding principles - you're applying them to new learning challenges.

Common Scaffolding Mistakes in Education

Understanding what not to do helps improve practice.

Over-Scaffolding

Providing too much support limits student growth. When you remove all challenge, you remove opportunities for thinking.

Students who receive excessive scaffolding can complete tasks but haven't developed understanding. They depend on your support rather than building internal capabilities.

The fix: Embrace productive struggle. Students should feel challenged but capable. If they're too comfortable, reduce support.

Permanent Scaffolds

When scaffolds never fade, they become accommodations or modifications. This isn't wrong - some students need permanent support. But call it what it is.

True scaffolding is temporary by design. If you're not planning to remove support, you're not scaffolding.

The fix: Always design scaffolds with a removal plan. If a student needs permanent support, that's different from scaffolding.

One-Size-Fits-All Support

Providing the same scaffold to all students ignores individual needs. Some students need minimal support while others require intensive scaffolding for the same task.

The fix: Differentiate scaffolds. Create tiered support systems where students access the level they need. This requires ongoing assessment and flexibility.

Scaffolding the Wrong Things

Sometimes we scaffold aspects of tasks that aren't the learning target. This wastes effort and confuses priorities.

For example, if the goal is analyzing themes in literature, don't scaffold decoding unless students can't access the text. The scaffold should match the learning objective.

The fix: Clarify what students need to learn, then scaffold only what prevents them from engaging with that learning. Remove obstacles to the actual learning goal.

Forgetting to Fade

The most common mistake: providing good initial scaffolds but never removing them. Students become dependent on support that was meant to be temporary.

The fix: Build fade plans into your lesson design from the start. Decide in advance how you'll know when to reduce support and what that reduction will look like.

Technology-Enhanced Scaffolding

Digital tools expand scaffolding possibilities and provide personalized support.

Adaptive Learning Software

Programs that adjust difficulty based on student performance provide individualized scaffolding at scale. Students receive appropriate challenge levels automatically.

These tools can offer immediate feedback, multiple representations, and varied practice opportunities. They supplement teacher instruction by providing additional scaffolded practice.

But technology shouldn't replace human scaffolding. It's most effective when integrated with teacher-designed support structures.

Collaborative Digital Tools

Online platforms enable peer scaffolding across time and space. Students share resources, provide feedback, and support each other's learning through digital collaboration.

Discussion boards, shared documents, and collaborative projects create opportunities for distributed scaffolding where multiple students contribute support.

Multimedia Scaffolds

Videos, animations, and interactive simulations can scaffold understanding of complex concepts. Students access these resources when needed, providing on-demand support.

The advantage: Students can revisit scaffolds multiple times, pause for processing, and move at their own pace.

Assessing Scaffolding Effectiveness

How do you know if your scaffolding is working?

Student Independence as the Key Metric

The ultimate measure: Can students complete similar tasks without support?

If students successfully transfer skills to new contexts without scaffolds, your scaffolding worked. If they remain dependent, something needs adjustment.

Document this progression through portfolios showing work with and without scaffolds, rubrics tracking independence, and observational records noting when support was needed.

Engagement and Confidence Levels

Effective scaffolds maintain student motivation and confidence while promoting challenge and growth.

Students should feel supported but not overwhelmed. They should tackle challenging work with increasing confidence over time.

If students avoid challenges, depend on you for all decisions, or quit when scaffolds aren't immediately available, the scaffolding may be creating dependence rather than building capacity.

Transfer and Application

The deepest measure: Can students apply learned strategies to new situations?

This demonstrates that scaffolds have been internalized. External supports have become internal capabilities. This is the goal.

Transfer doesn't happen automatically. It requires explicit instruction about when and how to use strategies across contexts. But scaffolding that builds genuine understanding enables this transfer.

What Scaffolding Requires of Teachers

Effective scaffolding is cognitively demanding work. It requires:

Ongoing assessment: Constant observation and analysis of student understanding to know what support is needed.

Flexibility: Willingness to adjust plans based on student responses rather than following rigid scripts.

Content expertise: Deep understanding of what you're teaching to identify precisely where students struggle and what support will help.

Patience: Comfort with student struggle and messiness of learning. Resistance to jumping in too quickly with help.

Planning: Deliberate design of support structures and fade plans, not just spontaneous helping.

This is sophisticated professional work. It's why scaffolding is harder than lecturing or assigning worksheets.

The industrial model treated teaching as knowledge delivery. Scaffolding recognizes teaching as the design and management of learning environments where students develop capabilities through strategic support. Explore professional development: Teacher Growth

Scaffolding and the Bigger Picture

Scaffolding assumes students are capable of complex thinking when properly supported. It positions teachers as designers of learning experiences rather than deliverers of content. It values independence and self-regulation as outcomes equal to content mastery.

These assumptions challenge traditional education models where teachers control learning and students follow directions. Scaffolding requires trusting students to do meaningful cognitive work - just with support while they build capacity.

The question isn't whether to provide support. It is whether we're building independence or dependence, developing capabilities or compliance and task completion.

Scaffolding, when implemented with intention and skill, builds the former. It develops students who can tackle challenges independently because we supported them strategically while they built that capacity.

That's the difference between helping and scaffolding. Helping gets the task done. Scaffolding builds the learner.